Indonesia: Emerging as a Leader in Aquaculture

EDITOR’S NOTE: As you’ll note on page 6 of this issue, ASIAN PACIFIC AQUACULTURE 2024 will be held i...

For those of us around in the late 1990s and early 2000s as members of the Minor Use and Minor Species (MUMS) coalition, there was probably nothing as significant or important as the effort to change the way we approve drugs and therapeutants for aquaculture animals. Until then all animals were treated the same when it came to getting a label through the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM), including a lengthy and cost-prohibitive approval process. All major species — domestic dogs and cats, cattle, pigs, horses and poultry — have markets large enough to justify the high costs of traditional labeling, but how do you get a drug for a parakeet, an alpaca or a dwarf cichlid? MUMS!

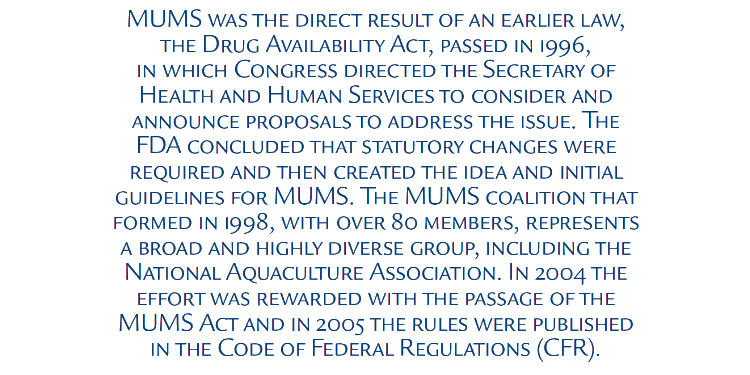

MUMS was the direct result of an earlier law, the Drug Availability Act, passed in 1996, in which Congress directed the Secretary of Health and Human Services to consider and announce proposals to address the issue. The FDA concluded that statutory changes were required and then created the idea and initial guidelines for MUMS. The MUMS coalition that formed in 1998, with over 80 members (Table 1, page 25), represents a broad and highly diverse group, including the National Aquaculture Association. In 2004 the effort was rewarded with the passage of the MUMS Act and in 2005 the rules were published in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR).

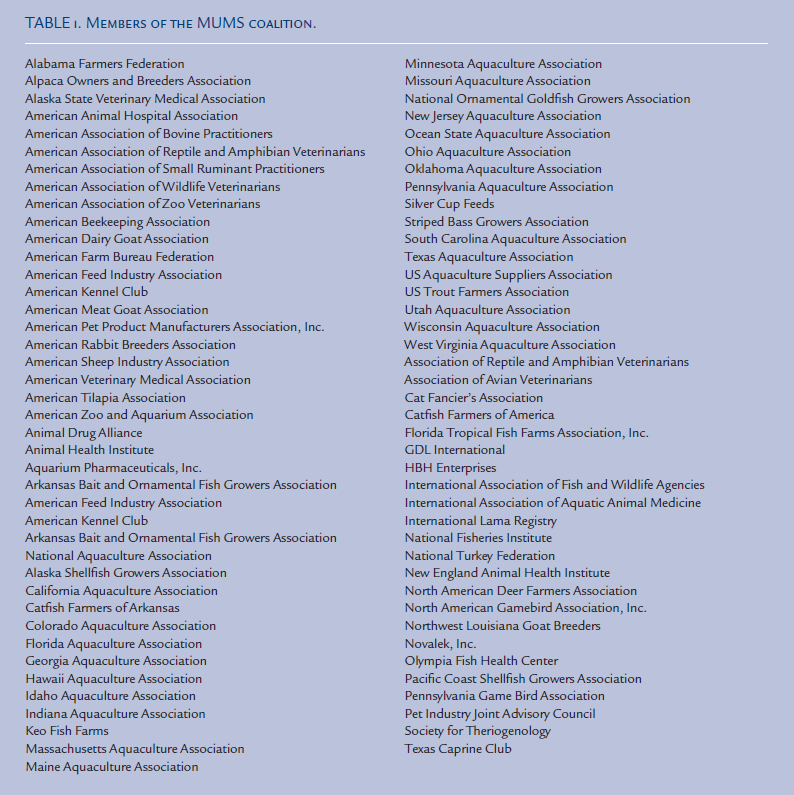

Perhaps one of the most important changes within MUMS was the inclusion of a provision for indexing products for minor species, which allows unapproved, legal use in non-food animals or in non-food life stages of food animals. Although indexing still required being able to demonstrate efficacy, human health safety and environmental safety, the review and approval process for indexing is much quicker and easier. However, after 14 years of MUMS, there are only 13 indexed products (Table 2, page 26) and only two of those are for aquaculture (Ovaprim and Aquacalm, both indexed for ornamental fish only). The FDA itself estimated a much higher number of indexed products when they were developing their final rules. Taken from the Federal Register Volume 72, Number 234 (72 FR 69107; 12/6//2007), FDA summarized their own expectations as follows:

Twelve years later that should amount to 240 indexed products, not the 13 we have now. So what happened, and more importantly how can we hope to finally enjoy the fruit of something as monumental as MUMS and the indexing process?

At the 25th annual Aquatic Animal Drug Approval Program (AADAP) meeting in July 2019, during a panel discussion dealing with a wide variety of topics, the question was asked why aren’t there more indexed drugs for non-food life stages of foodfish, including broodstock. The authoritative response from the Director of the Office of MUMS was that this option was deemed ineligible many years ago and that the reason was not a policy decision but embedded in the law itself.

Because my focus is on ornamental aquaculture, the designation that broodstock of foodfish were ineligible for indexing wasn’t a huge concern of mine or my main clients. Like others I just assumed that, if FDA CVM says the law doesn’t allow it, then that’s the end of the conversation. However, given the failure to get legal products for aquaculture approved faster and cheaper since MUMS passed, I decided to investigate this statement further. What I found was that it is FDA’s interpretation of the law that is the impediment to indexing many of the products. Below are a few relevant sections of the law and the policy. The first two are the text found in the Act itself and the subsequent Code of Federal Regulations. The third is text in a Guidance for Industry document from CVM, essentially their policy.

The Secretary shall establish an index limited to - (a)(1) (A) new animal drugs intended for use in a minor species for which there is reasonable certainty (emphasis added) that the animal or edible products from the animal will not be consumed by humans or food-producing animals; and (B) new animal drugs intended for use only in a hatchery, tank, pond, or other similar contained man-made structure in an early, non-food life stage of a food-producing minor species where safety for humans is demonstrated in accordance with the standard of section 512(d) (including, for an antimicrobial new animal drug, with respect to antimicrobial resistance).

…This index is only available for new animal drugs intended for use in a minor species where there is a reasonable certainty (emphasis added) that the animal or edible products from the animal will not be consumed by humans or food-producing animals and for new animal drugs intended for use only in a hatchery, tank, pond, or other similar man-made structure in an early, non-food life stage of a food-producing minor species, where safety for humans is demonstrated in accordance with the standard of section 512(d) of the Act (including, for an antimicrobial new animal drug, with respect to antimicrobial resistance).…

Only new animal drugs intended for use in non-food producing minor species are eligible for indexing, except that new animal drugs intended for use in early, non-food life stages of some food producing minor species may be eligible for indexing under very limited circumstances (emphasis added). (Sec. 572(a)(1) of the Act) (21 U.S.C. 360ccc-1(a)(1)).

The problem appears that the law starts out with the term “minor species” and then talks about the “animal” and “edible products.” Current policy has determined that the entire species, not the animal being treated, is what determines eligibility for indexing and has gone on to conclude that edible products include any resulting offspring. If someone ever eats that species, or feeds that species to another food-producing animal, then no animals within that species are eligible for indexing, including broodstock.

However, one can also read this section to say that indexing is not available for major species and that it is the animal being treated or its edible products that allow or disallow indexing. Further, since we can recognize early life stages as non-food, it seems reasonable that offspring should not be considered as edible products of the animal except where there is reasonable certainty that the product may remain or cause health considerations in those offspring.

The choice of how to transfer the law into policy and guidance can also be seen in the policy guidelines where the term “reasonable certainty” no longer is used and the term “very limited circumstances” has been added. I assert that this is a large reason why we have 13 and not 240 indexed products.

Within many individual minor species are animals that, with reasonable certainty, will or will not be eaten by humans or other food-producing animals, depending on their life stage or production circumstances. Aquacultural practices, especially commercial aquaculture, include clear cases where this is true within a species. In almost all cases, broodfish are not eaten, sold as food or fed to food-producing animals. Eggs and larvae in a hatchery are not eaten, sold as food or fed to food-producing animals, something actually recognized in law and policy.

Even with caviar-producing species, eggs collected for spawning are treated differently than those going on a plate of food. Eggs for caviar are almost always harvested before they ovulate and are never fertilized or allowed to incubate and are subject to strict federal and state food safety HACCP regulations. Treatments for incubating and hatching eggs therefore have a strong reasonable certainty of not being used for caviar. For example, if a gravid female Russian sturgeon Acipenser gueldenstaedtii is going to be harvested for caviar, that animal and her edible products are ineligible for indexing. However, if eggs or other early life stages from another Russian sturgeon need to be treated for fungus in the hatchery, indexing should be allowed. Beyond aquaculture there are numerous examples where a minor species has animals that are food in one situation but not in another (e.g. a pet rabbit or a rabbit being raised as food, a deer for venison production or a deer in a zoo).

The assertion that a treatment used on broodstock for a food species, especially for inducing reproduction, will become a human food safety issue when the offspring are sold is based on a zero-risk approach and not the facts. Research on modern products to induce ovulation or spermiation in broodstock has shown that these products clear the bloodstream of sexually mature fish quickly, are not transferred to gametes or embryos and thus have no reasonable way to directly impact the resulting offspring and their meat. Other broodstock treatments, especially those used after spawning, also have little to no risk of being transferred to gametes and therefore the resulting offspring need not be considered as edible products. If and when there is a legitimate, science-based argument to the contrary, eligibility for indexing can and should be denied, but not without such evidence. Edible products should be restricted to only the actual parts of the animal that might be eaten, including eggs within a female, and not extended to the next generation.

The MUMS Act and agency policy recognize that treatments of eggs, larvae and even fingerlings are less likely to impart a health risk to the product when harvested months or years later and indexing has clearly been allowed by defining these as non-food life stages. However, by restricting this option to “very limited circumstances,” we have failed to fully achieve what is possible under the law. If the law allows indexing for early life stages where safety for humans is demonstrated, why change that to very limited circumstances?

As an interesting and admittedly extreme example, one of the longest running Investigative New Animal Drug (INAD) projects is for the use of 17α-methyltestosterone (MT) to masculinize first-feeding tilapia. For the first 21 days of feeding, they are provided with feeds that contain 60 mg MT/kg feed. Studies indicate that levels return to normal within weeks of termination of feeding MT. Depending on temperature and culture methods, the resulting crop of all-male fish is harvested for food a year or more later. Would full approval as a new animal drug provide any reduction of the risk or provide any more reasonable certainty that those tilapia fry will not be eaten compared to simply indexing?

Indexing requires the creation of an expert panel to review the request, the pertinent literature available and make a recommendation for final label instructions. Reasonable certainty that the animal and any edible products are not used for human food or fed to a food-producing animal should be a separate section of the expert panel’s responsibility, including recommendations on labeling language to assure this. Having served on both expert panels for the only two indexed drugs for aquaculture, I can attest that that was part of our duties and is clearly reflected in the final index labels. Accusations that someone might eat an animal are often the result of lack of understanding of the realities of commercial aquaculture, a situation that is addressed by having true experts in aquaculture serve on these panels. If there is concern about a product used on broodstock being a human health risk in the resulting offspring, the expert panel should include a fish physiologist or endocrinologist to specifically address the risks of vertical transfer.

LawLabels are the law in the US and are the crux of the problem that created MUMS in the first place. Index labels are not an approval by FDA but simply provide legal access to a product. To provide reasonable certainty that the animal being treated and its edible products will not be used for food, labels for indexes might read:

This product is only to be used in species X where there is reasonable certainty that the animal and its edible products will not be used for human consumption or fed to another food-producing animal.If someone violates that label, the crime, and thus the liability is squarely on them. Labels for drugs, pesticides and many other chemicals used daily include language designed to address the risks with improper or unapproved applications and provide the reasonable certainty that an agency like CVM or a product sponsor needs to protect their liability.

Many more products for treating broodstock, eggs and other early, non-food life stages for aquaculture could be indexed if the language of the law is used to inform approval decision-making. If a sponsor can demonstrate, with reasonable certainty, that the animal being treated will not be eaten, sold as human food or used as food for a food-producing animal, CVM should embrace the request for indexing and not reject it. Index labels can easily include specific language to further provide the reasonable certainty needed to move forward.

Congress, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, the MUMS coalition and CVM staff worked together to develop a new paradigm for getting products legally available for not just aquaculture but the myriad other animals that are deemed minor species. To have only 13 indexed products, not 240, 14 years after MUMS became law, is a disappointment for everyone involved, and if the failure is due to policy and not the law, this policy should be abandoned.

While the MUMS coalition participated in early versions of the Act, it was primarily written by CVM and other federal staff. Their careful choice of wording was typical of such an effort. Instead of looking at only non-food early life stages, under very limited circumstances, let’s consider and approve index labels when there is reasonable certainty that the compound won’t enter the human food chain as the law clearly intended.

Notes: Craig Watson, Director – Tropical Aquaculture Laboratory, University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, 1408 24th Street SE Ruskin, FL 33570, Author email: cawatson@ufl.edu

In addition to his role as Director of the University of Florida’s Tropical Aquaculture Laboratory, Craig Watson also serves on the Board of Directors of the National Aquaculture Association, which supports the recommended change in CVM’s interpretation of the law for indexing.