Indonesia: Emerging as a Leader in Aquaculture

EDITOR’S NOTE: As you’ll note on page 6 of this issue, ASIAN PACIFIC AQUACULTURE 2024 will be held i...

To use a quote from the famous explorer Jacques Cousteau in 1971: “We must plant the sea and herd its animals using the sea as farmers instead of hunters. That is what civilization is all about — farming replacing hunting.” Well, as it turns out, this farming of the seas began on the North American continent hundreds if not thousands of years ago with First Nations and indigenous peoples ranching and carefully managing local seafood resources in a sustainable farming fashion.

Fast forward to the 1800s and European settlers, in what is now known as Canada, began restorative aquaculture primarily for pond and lake enhancement of freshwater salmonid stocks for sport fisheries using basic aquaculture techniques. The first marine finfish hatchery in North America (cod incubation and release of fry) was established over several years in the 1880s by a Norwegian scientist, who released billions of small fish into the Atlantic Ocean in Newfoundland with the hopes of enhancing local stocks that had plummeted in the previous decades.

In the early 1900s, attempts to restore a variety of dwindling natural stocks on the East and West Coasts of Canada introduced the Pacific oyster, the Manila clam and several other species to the West Coast of Canada and several other non-native species of finfish and shellfish to the East coast — all with the express purpose of rejuvenating dwindling native seafood stocks or enhancing fishery productivity for recreational or commercial purposes across the nation. All of these “restorative aquaculture efforts” employed fairly well-established freshwater and saltwater hatchery-nursery principles of aquaculture (read: enhancement) developed by Europeans and Asians and adapted to Canadian conditions.

It was not until the second part of the last century, in the 1960s, roughly six decades ago, that Canadian scientists with the Fisheries Research Board of Canada (Fisheries and Oceans predecessor), local universities inland and on the coasts, and provincial governments started to experiment with production techniques of various native and non-native freshwater and saltwater species of animals and plants for commercial aquaculture purposes, to create sustainable seafood farming industries from coast to coast to coast.

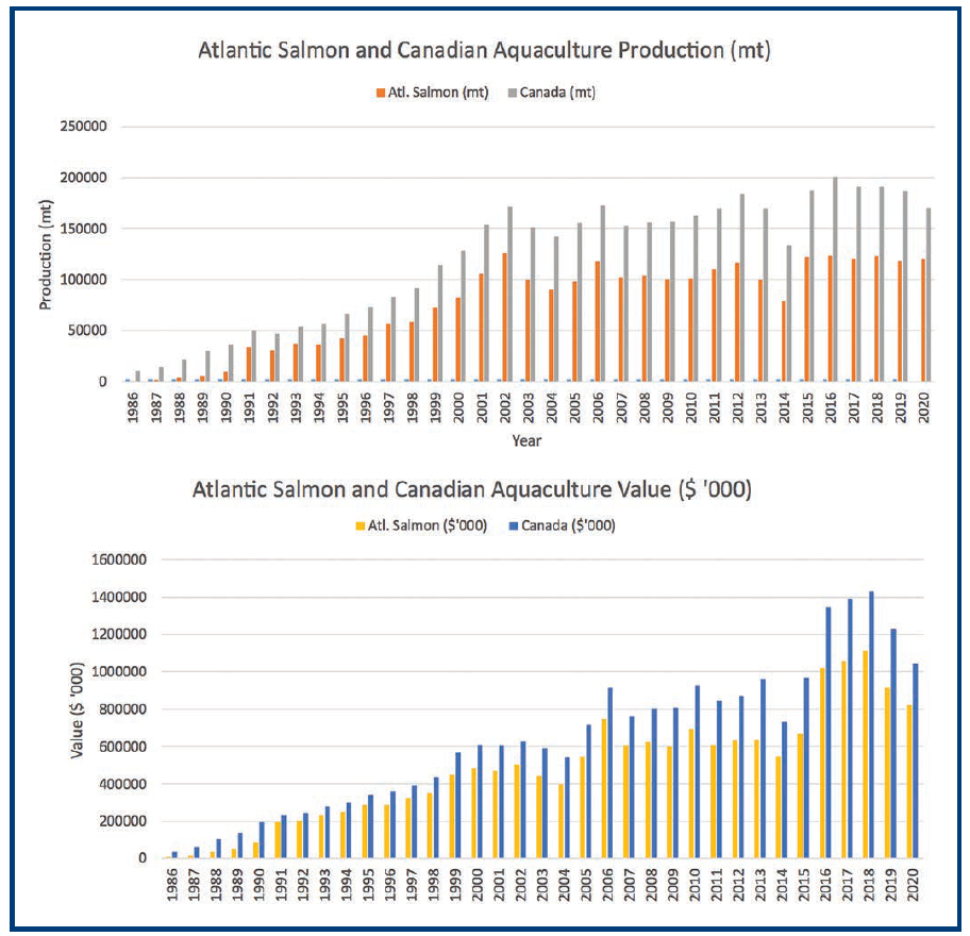

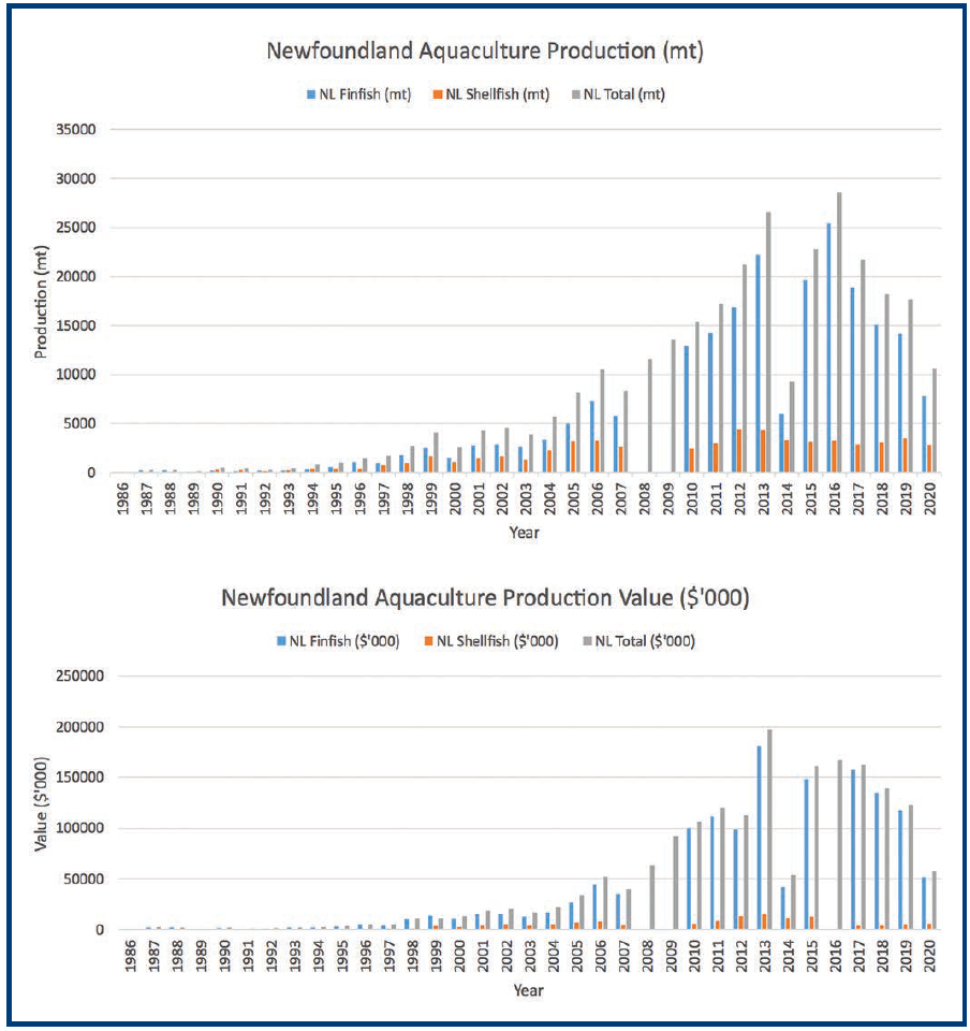

Canada is blessed with an abundance of freshwater and relatively pristine coastal waters spanning three oceans. The productive area for commercial seafood farming is barely used by aquaculture, with less than 1 percent of the suitable farming areas utilized for commercial farming purposes. Once in the top ten “fishery” nations in terms of productivity, based on landings of seafood in the 1980s, Canada now sits around 22nd globally, in terms of production of seafood. Arguably, if it was not for aquaculture growth in the past four decades (see Fig. 1 for production levels), we would be much further behind. Most seafood-producing countries have embraced sustainable aquaculture as the future of food production globally to provide environmental, social and economic opportunities to over 20 million farmers (FAO 2020). There are currently over 3 billion seafood meals consumed daily by the 8 billion citizens of the planet, of which more than 50 percent comes from aquaculture. This is expected to grow over the next decades as humanity searches for sustainable solutions for food security and supply, and aquaculture will play a major role.

Did You Know? — Canada Leads

- The first marine finfish hatchery in Canada was in Dildo, Newfoundland, for cod in the 1880s.

- The world’s first sea scallop Placopecten magellanicus farm was in Little Mortier Bay, Newfoundland and Labrador in 1981.

- The first genetically engineered fish for food was created in a lab in the mid-1980s at Memorial University in NL.

- The world’s first commercial-scale marine finfish hatchery for cod was in Newfoundland in 1997 but an electrical mishap burned it to the ground.

- The first ever shellfish processing plant to be certified to the Best Aquaculture Practices (BAP) standard was in Newfoundland, as was the first 4-star Atlantic salmon operation, and PEI had the first BAP-certified mussel farm.

- North America’s first organically certified blue mussels came from Newfoundland, to be followed closely by organic mussels from PEI.

- Canada is the leading producer of Arctic charr eggs.

- A small family salmon farming operation that started in 1985 in New Brunswick is now one of top five seafood farming companies in the world, farming shrimp, bream, bass and salmon, with production facilities in Europe, Canada, South and Central America.

- The world-leading commercial land-based seaweed farm is located in Nova Scotia, and is a provider of algal extracts, nutraceuticals, cosmetics, animal and human food.

Today, there are commercial seafood farming operations in all ten Canadian provinces, and at least 1 of its 3 territories, with over a dozen species at the commercial or pre-commercial stages of production. Species range from eels, scallops, oysters, mussels, clams, seaweeds (several species), phytoplankton, to trout, charr, salmon, whitefish, black cod (sablefish), and several others in various stages of development, including sea cucumbers, sea urchins, seaweeds and others.

The principal species of farmed seafood, making up the bulk of production (95 percent by volume), in Canada consists of Atlantic salmon, blue mussels, oysters (Eastern and Pacific species) and rainbow trout, with several others showing promise. Production facilities include recirculating aquaculture systems and hatchery-nurseries for on-land production of “seedlings,” net-pen and longline systems for open waters and even ponds for seasonal ongrowing.

Today, commercial aquaculture in Canada is a thriving sector employing over 20,000 Canadians in the production process from egg to plate. The sector is relatively young, speaking demographically, and about 30 percent are women in various positions. There are in excess of 50 First Nations participating in the aquaculture sector in Canada. These First Nations are either sole-enterprise owners or operate in partnership with their local communities in farming, processing or supplier activities.

Few people would know that, in the 1960s, Canadian government scientists, as well as a handful of academics, were intimately involved in the underlying experiments and trials for commercial Atlantic salmon, scallop and mussel farming with young entrepreneurs and academics in Europe, Norway and Canada, to try and bring aquaculture to the world. These efforts continue today with various academic and government labs continuing to provide support and innovation in fish nutrition, fish health, production technologies, environmental mitigation, new product and process development, genetics and genomics, breeding and climate-adaptation. Moreover, much of the innovation and trials on farming seafood in Canada’s Northern climate, which is literally frozen in ice in the winter in many places, has been from home-grown solutions through the entrepreneurial spirit by industry pioneers — it’s not easy farming in the ocean or on land when the ice is 1-m thick! Innovation and adaptation are the keys to success. Winter harvesting below the ice, submersible longlines and ice-booms are just some of the innovations seafood farmers have adapted so they can supply fresh products year-round.

The sector has always been innovative, always seeking solutions, using science and technology in partnership with governments, universities, research organizations and the private sector to find those solutions. Fish health management is a major challenge for aquaculture worldwide, so leading scientists on Canada’s east and west coasts, along with aquaculture companies, are developing a variety of tools to combat the principal scourges from microbial and parasitic pathogens (cleaner fish, vaccines, pre- and pro-biotic feed supplements). As well, climate change and global warming are a worldwide threat to all seafood farmers and there are Canadian teams leading the charge on adapting to production vagaries in the sector, among other challenges.

Unfortunately, Canada continues to fall behind in terms of production of farmed seafood, compared to its competitors. There has been no overall growth in production in that last twenty years. There are indeed challenges with the regulatory frame and there is limited support for research, development and innovation, compared with other countries, so efforts to improve matters have been the subject of vigorous advocacy for about two decades. The real challenge is to take advantage of the opportunity to grow the sector in today’s framework of social, environmental and economic sustainability and to become a top-5 leader in the Blue Economy of the future. With our abundant natural resources, ingenuity and some fortitude, there is no reason why Canada cannot become a global leader in science and production of sustainable farmed seafood. Aquaculture Canada and

Many of the innovations and updates on Canadian and global aquaculture will be presented at the upcoming international conference entitled “The Leading Edge of Food Production” to be held in historic St. John’s, NL, Canada from 15-18 August 2022. The conference is being organized by the Newfoundland Aquaculture Industry Association, the Aquaculture Association of Canada and the World Aquaculture Society, and they look forward to welcoming delegates from around the world. To date, the trade show is sold out, and delegates from over 20 countries are expected to show. There will be somewhere in the vicinity of 400 presentations on topics ranging from policy and regulation to the science and innovation of aquaculture. Over 600 delegates are registered to date, with room to grow. This will be the largest aquaculture conference ever held in Newfoundland and Labrador, and the largest conference and trade show in Canada on the subject in over three decades.

For naturalists and historians, the area is quite bountiful with marine life with puffins, whales, fish and bird sanctuaries all within an hour or two of the city, so plan to spend at least one day visiting the area. There may even be some icebergs still remaining just a few hours away, for the real tourists. Pubs and eateries abound near the conference center (some reminiscent of Bourbon Street in New Orleans) where live music is played nightly. St. John’s is North America’s “oldest city,” with a mixture of Old and New World charm. It is also at the most easterly point in the Americas, where the sun rises first over the ocean. We look forward to welcoming you to the city on the edge of the continent.